Historical Adoption of Icing in Baseball

The practice of icing sore arms became entrenched in baseball culture in the late 20th century. It gained prominence in the 1960s as star pitchers like Sandy Koufax were famously photographed soaking their pitching arm in ice after games. This visible example helped make icing a standard post-game recovery ritual for pitchers, under the belief that it would reduce pain and prevent soreness.

In 1978, Dr. Gabe Mirkin – a Harvard physician – introduced the RICE protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) as a guideline for treating athletic injuries. From the late 1970s through the 2000s, icing was widely recommended by coaches and trainers for pitchers after outings to reduce inflammation and numb soreness. By the 1980s and 90s, it was commonplace to see Major League pitchers with ice packs saran-wrapped to their shoulders or elbows after they left the mound. Icing had become synonymous with proper recovery. Ironically, decades later Dr. Mirkin would retract his advocacy of ice, as new evidence emerged – a point we will revisit.

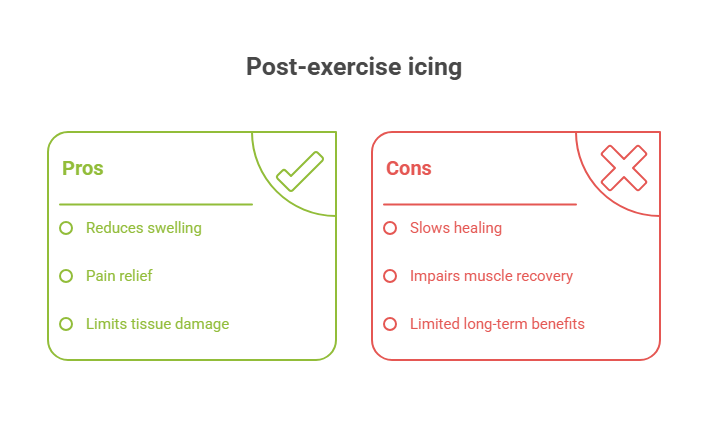

Physiological Effects of Icing: Benefits and Drawbacks

The rationale behind post-exercise icing was straightforward: control the body’s inflammatory response and relieve pain. Cold application causes blood vessels to constrict, theoretically limiting swelling and tissue bleeding in the stressed area. In acute trauma (like a sprain or bruise), icing can indeed slow tissue metabolism and potentially reduce secondary cell death by limiting blood flow and cooling the area. Ice also has a well-known analgesic effect – it numbs nerve endings, providing short-term pain relief and comfort to the athlete. These perceived benefits made ice a fixture in recovery protocols for many years.

However, contemporary research has increasingly shown that these short-term effects do not translate into faster healing or better muscle recovery. In fact, scientists have identified several significant drawbacks to icing muscles after intense exercise. To understand why the consensus is shifting, it’s important to examine what icing actually does physiologically:

Purported Benefits of Icing:

- Pain reduction: Numbing effect provides immediate relief from soreness or throbbing.

- Reduced acute swelling: Vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) may temporarily limit fluid accumulation and internal bleeding in an injured area.

- Slowed cell metabolism: Cooling tissues can slow down cellular activity, which proponents believed might lessen secondary tissue damage in cases of severe trauma.

Documented Drawbacks of Icing (from research):

- Delays healing inflammation: Icing blunts the normal inflammatory response that initiates repair. A 2010 study showed inflammation is necessary to heal muscle damage; blocking it (with ice or anti-inflammatories) delays healing by preventing the release of key growth factors like IGF-1.

- Reduced blood flow and nutrient delivery: Cold constricts local blood vessels so much that far less “healing fluid” (oxygenated blood, nutrients, and immune cells) reaches the muscle. One study found that topical cooling after exercise significantly limits the flow of regenerative fluids to the area and slows recovery from muscle damage.

- Prolonged swelling (lymphatic backflow): Applying ice can actually increase edema. Research in 1986 demonstrated that after about 20 minutes of icing, lymphatic vessels become more permeable, causing fluid to leak back into tissues. Thus, extended icing can lead to increased local swelling, not less.

- Risk of tissue damage from ischemia: Excessive vasoconstriction means healthy cells adjacent to the injury may be starved of blood. A 2015 study noted that intense cold-induced vasoconstriction can kill otherwise healthy tissue by depriving it of oxygen.

- Impaired strength and adaptation: Post-workout icing has been shown to impede muscle recovery and adaptation. Athletes who routinely iced after exercise experienced slower restoration of strength and diminished gains in muscle size and power. For example, immersing muscles in ice water immediately after a hard workout substantially reduces the cellular signals for building stronger muscle, blunting gains in muscle mass and strength. Over a season, a pitcher who ices constantly could potentially see greater losses in shoulder muscle strength due to this stunting of the normal rebuilding process

In summary, while icing can make a pitcher feel better in the immediate aftermath of an outing (through numbing and placebo effect), it does not actually speed up muscle repair – and may do the opposite. No published peer-reviewed study has definitively shown that icing improves healing; on the contrary, many findings indicate ice delays recovery, increases swelling, and even causes additional damage in some cases. The very inflammation that icing aims to reduce is, in fact, crucial for muscle regeneration, delivering nutrients and repair cells to micro-tears in muscle fibers. Suppressing that process with cold therapy short-circuits the body’s natural healing cycle.

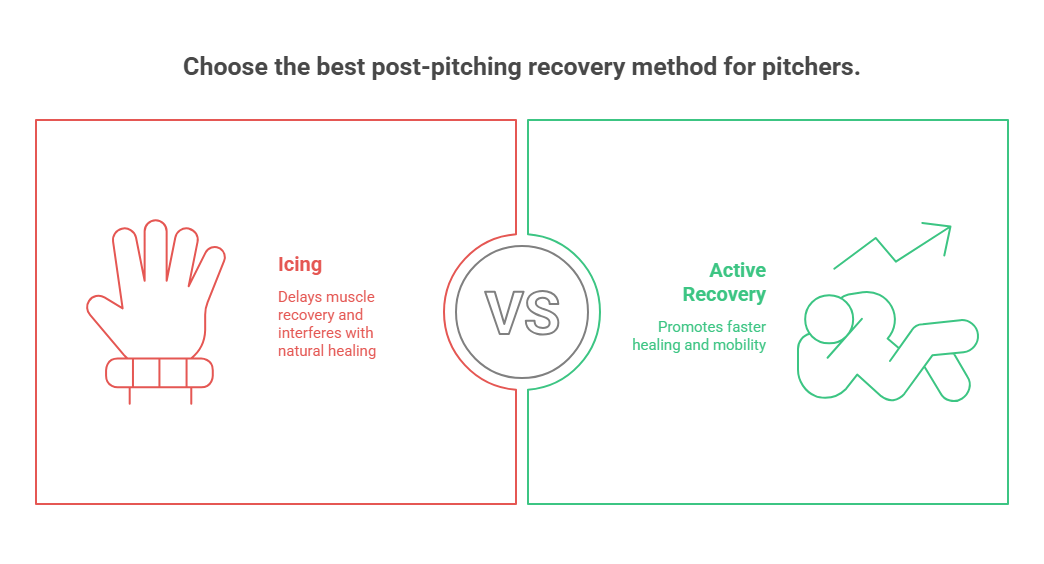

The Shift Away from Icing: Modern Criticisms and Alternatives

By the 2010s, given the mounting evidence, many sports medicine professionals began actively questioning the old ice-after-exercise dogma. Notably, Dr. Gabe Mirkin – the originator of RICE – reversed his stance on icing. In a 2014 update, Mirkin acknowledged, “Subsequent research shows that rest and ice can actually delay recovery.” He explained that the immune system needs the inflammation response to heal, and icing only dampens this necessary process. Ice can provide temporary pain relief, Mirkin conceded, but it ultimately slows healing – meaning athletes may feel better yet actually recover more slowly.

Other experts have echoed these criticisms. Gary Reinl, author of Iced! The Illusionary Treatment Option, became one of the most vocal proponents of abolishing routine icing. Reinl draws a sharp distinction between inflammation (which is beneficial and necessary for healing) and swelling (the excess fluid that can accumulate afterward). He argues that inflammation is the body’s repair mechanism, whereas swelling is only harmful if it stagnates. According to Reinl, icing an injury or sore arm and then sitting still is exactly the wrong approach – it prevents the lymphatic system from clearing out fluid and debris, allowing swelling to linger and even “suffocate” healthy tissues. In his view, the key is to get things moving: “Muscle activation is the best mechanism to reduce congestion and swelling,” he says, meaning gentle movement or muscle stimulation is needed to actually remove the fluids, not ice.

Leading physical therapists and athletic trainers have accordingly shifted toward movement-based recovery protocols. Dr. Kelly Starrett, a prominent PT and author, famously stated that “either you don’t understand the healing process, or ice is the wrong way to facilitate it”. He promotes a “movement is medicine” philosophy: even for acute injuries, after initial stabilisation, early controlled motion is encouraged over long periods of rest and icing. Starrett notes that muscle contractions (even very mild ones) are what pump waste out of tissues and bring fresh blood in, so “movement is the best way to reduce swelling and return athletes to ready-state levels.”

In practice, if an area is too painful to move actively, therapists will use neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) devices to create painless, non-fatiguing muscle twitches in the injured area. This achieves a pumping effect similar to movement, activating lymphatic drainage without stressing the tissues. Starrett also often combines compression therapy with such muscle stimulation, and recommends natural anti-inflammatories (like turmeric and fish oil) for pain management in lieu of ice or NSAIDs. His postoperative patients – from ACL tears to fracture repairs – are put on an immediate “decongestion protocol” involving whatever movement they can tolerate, rather than icing and immobilization. The results, he reports, have been faster recoveries without the need for ice at all.

Within baseball, a similar re-examination has been underway. Some progressive pitching coaches and training programs began to abandon the ice bag in favor of active recovery methods. For example, Driveline Baseball – a well-known pitching performance and research facility – openly rejects passive icing as a recovery tool. Their staff emphasizes active cooldowns and circulation-boosting techniques immediately post-throwing, such as light exercise and electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), instead of wrapping a pitcher’s arm in ice. Driveline’s founder noted that they do not generally embrace cold therapy for healthy pitchers; they only resort to targeted cold with compression in special cases (e.g. a pitcher rehabbing from surgery who has significant acute inflammation). In those instances, using a device that combines ice and cyclical compression can help manage severe post-surgical swelling, but even then it’s paired with muscle stimulation to keep fluid moving. This nuanced approach highlights that routine post-pitch icing is no longer the default – even trainers who still use ice are augmenting it with techniques to counteract ice’s downsides (such as combining it with intermittent compression and movement).

Many professional pitchers themselves have stopped automatically icing their arms after games. Instead, they are opting for “active recovery” routines that increase circulation and mobilize the arm. For instance, some teams now equip players with portable NMES devices like the Marc Pro, which causes gentle muscle contractions in the shoulder and forearm to flush out waste products and relieve soreness without taxing the arm. Rather than sit still with an ice wrap, a pitcher might hook up to a low-frequency stim unit or perform light shoulder exercises. Heat therapy has even been revisited – in contrast to icing, applying mild heat (or contrast showers) post-throwing can dilate blood vessels and promote blood flow, which may assist recovery by speeding up metabolite clearance. The overall trend is that movement, not immobilization, is the centerpiece of modern recovery. As one baseball training blog quips, this is a shift from the old wisdom of “put ice on it” to a new mantra of “get moving (safely) and let the body heal itself.”

Finally, it’s worth noting that ice hasn’t been completely banished – it still has a role for acute injury first aid or pain management in specific scenarios. But the blanket prescription of “ice every arm after every outing” is fading fast. Even youth pitching programs have started educating players that icing for routine soreness is unnecessary and might even be counterproductive. The consensus among many in the baseball sports medicine community today is that if an arm needs to be iced to handle the workload, something else is wrong – either the pitcher is injured or their recovery routine needs improvement. In those cases, the priority should be addressing the root cause (mechanics, conditioning, or health) rather than simply numbing it with ice.

Current Best Practices for Pitcher Recovery

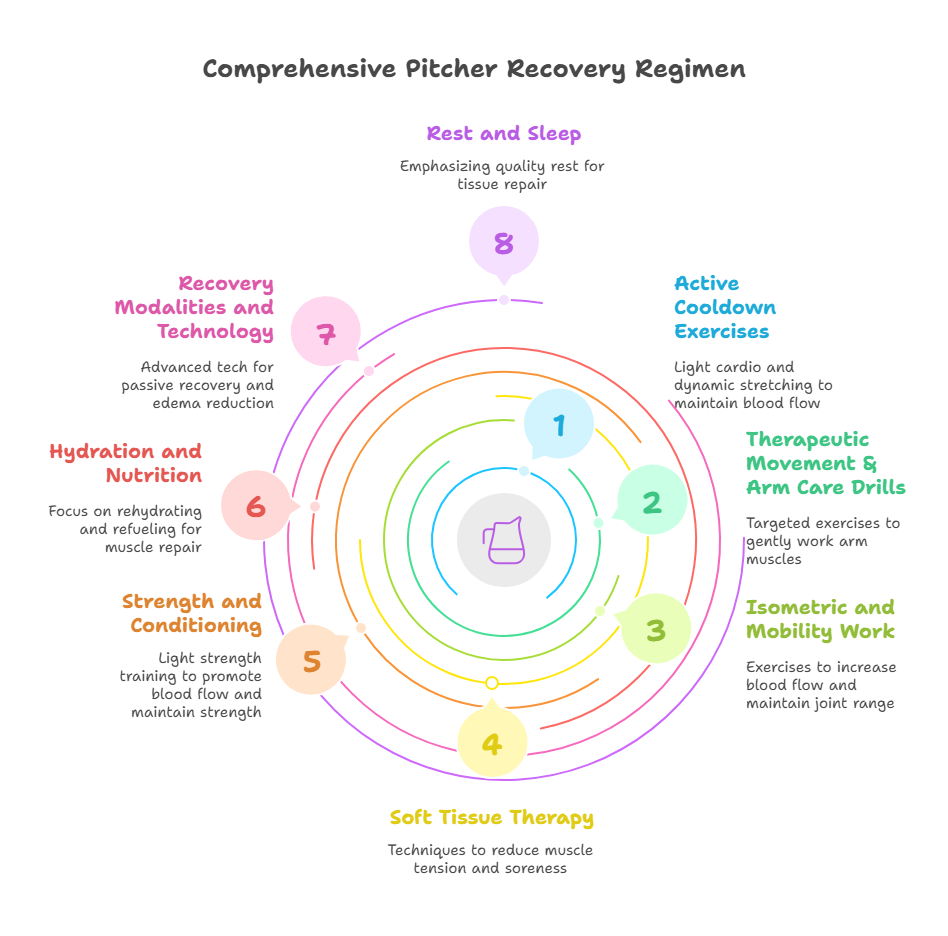

In light of the above shifts, current best-practice recovery protocols for baseball pitchers have become much more comprehensive and active. Major League Baseball organizations and advanced pitching development programs now tend to emphasize active recovery, conditioning, and holistic athlete care over quick fixes. Below are common elements of a modern pitcher recovery regimen (used in various combinations by teams and training programs):

- Active cooldown exercises: Instead of immediately immobilizing the arm, pitchers keep the blood flowing right after they throw. This might include a few minutes of light cardio (e.g. stationary bike or light jogging) and dynamic stretching. Notably, the old practice of running lengthy “poles” (long-distance laps) to flush lactic acid has been largely abandoned – research shows lactic acid is not the cause of post-pitching fatigue, and long slow runs can actually reduce power output without aiding recovery. A short, low-intensity aerobic flush is fine, but excessive long-distance running is discouraged.

- Therapeutic movement & arm care drills: Pitchers now engage in targeted arm exercises to gently work the shoulder and arm muscles after an outing. Commonly, teams employ resistance band routines (such as J-bands or tubing exercises popularized by pitching coaches) to take the shoulder through ranges of motion post-throwing and increase blood flow to the area. Light throwing or “rehab catch” on the day after a start is also used by some – the pitcher might make very easy, pain-free throws just to stimulate tissue loading and circulation, as loading damaged tissue (within tolerance) has been shown to accelerate healing. The key is low-intensity, non-fatiguing movement that signals the body to recover.

- Isometric and mobility work: Many programs incorporate isometric exercises (muscle contractions without movement) for the arm and shoulder as a recovery tool. Holding certain positions (for example, gentle planks or light dumbbell holds at various arm angles) can increase blood flow and activate stabilizing muscles without causing further micro-tears. These exercises also help maintain joint range of motion. Along with isometrics, mobility drills (controlled arm circles, scapular stretches, etc.) keep the shoulder complex from tightening up after heavy use.

- Soft tissue therapy: Massage, foam rolling, and other soft-tissue techniques are now standard parts of recovery. Pitchers will often use a foam roller or lacrosse ball on their back, shoulder, and arm musculature after pitching to reduce muscle tension and soreness. Studies support that soft tissue work can improve short-term range of motion and may help diminish delayed muscle soreness. Some teams have massage therapists or use tools like percussive massage guns on pitchers’ arms post-game to aid circulation.

- Strength and conditioning (next-day): Rather than avoiding all exercise, many pitching coaches advise a light strength training session the day after a start. This might seem counterintuitive, but doing controlled weightlifting for the legs and core (and even some upper-body and rotator cuff exercises) the next day can promote blood flow and maintain overall strength balance. For example, a day-after routine could include moderate squats, lunges, rows, and shoulder exercises at low intensity. This active approach helps the body recover faster than if the pitcher were completely sedentary. Of course, if a pitcher is very sore, this is adjusted to their tolerance (the mantra is “active recovery, not excessive fatigue”).

- Hydration and nutrition: Professional pitchers pay much closer attention now to rehydrating and refueling immediately after an outing. Fluid and electrolyte replacement helps muscle tissue recover and prevents cramps. Nutritionally, ensuring adequate protein and healthy carbohydrates post-game supports muscle repair. Some teams also encourage natural anti-inflammatory foods or supplements – for instance, turmeric and omega-3 fish oil – which have been shown to modestly reduce muscle soreness and pain without impeding the healing process. In contrast, routine use of NSAID medications (like ibuprofen) is often discouraged for recovery, since, similar to ice, they can blunt the beneficial inflammatory response and have been correlated with injury when overused.

- Recovery modalities and technology: Pitchers now have access to advanced recovery tech that goes beyond a simple ice pack. Compression sleeves or pneumatic compression devices (like arm sleeves that periodically squeeze the arm) can help mechanically pump out edema in the arm. Some pitchers use these in combination with cooling only if significant swelling is present, as it provides cold without static immobilization (examples include devices like the PowerPlay or Game Ready systems). Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) devices (e.g. Marc Pro) are widely used to create gentle contractions in the arm muscles, essentially mimicking light exercise to flush waste products and bring in fresh blood. These gadgets allow a pitcher to passively recover while still achieving the benefits of muscle activity. Additionally, many teams utilize contrast therapy (alternating hot and cold water immersion) or cryotherapy chambers for full-body recovery, though these are applied judiciously (often for perceived recovery or pain relief on short turnarounds, rather than as daily practice). Crucially, all these modalities are seen as adjuncts to, not replacements for, the fundamental recovery principles of movement, sleep, and nutrition.

- Rest and sleep: Finally, the simplest (yet often undervalued) aspect of recovery is quality rest. Professional pitching programs heavily emphasize getting sufficient sleep, especially after a start, as that is when the body’s hormonal environment is primed for tissue repair. It’s now well-recognized that no amount of icing or high-tech gadgetry can compensate for lack of sleep or poor overall recovery habits. Thus, teams instill in pitchers the importance of good sleep hygiene, rest days, and listening to their body’s signals of fatigue. Recovery is viewed as a 24/7 process encompassing lifestyle – pitchers are coached on everything from post-game meal choices to stress management, all aimed at enabling their arm to bounce back for the next outing.

These current best practices represent a far more active and comprehensive approach to pitcher recovery than the traditional “ice and rest” method. By focusing on maintaining blood flow, promoting muscle repair, and addressing the pitcher’s whole-body needs (not just the arm in isolation), modern programs aim to both speed up recovery and improve long-term performance. Notably, many of these practices are now standard in Major League clubhouses. It’s not unusual, for example, to see a starting pitcher head to the exercise bike and arm band station after he’s pulled from a game, rather than straight to the trainer’s table for an ice wrap. Pitchers and coaches have largely embraced the notion that an active arm is a healthy arm, especially in the 24–48 hours following an outing. This holistic recovery strategy is believed to reduce injury risk and facilitate the incremental gains in strength and endurance that pitchers need over a long season.

Insights from Other Sports on Muscle Recovery

Baseball’s evolving perspective on icing is mirrored by trends in other sports. For decades, athletes across disciplines have used cold therapy in hopes of speeding up recovery. Marathon runners would take ice baths after long runs; football and rugby teams commonly plunged into tubs of ice water the day after games; and elite soccer clubs have installed cryotherapy chambers for players. The underlying idea was always the same – reduce inflammation, numb soreness, and the athlete will feel rejuvenated for the next effort. However, sports science research in recent years has prompted a more nuanced view, and many sports are reconsidering how and when to apply ice.

Notably, in strength and power sports, the use of post-workout ice has come under scrutiny for blunting training adaptations. Studies with weightlifters have shown that routine cold-water immersion after lifting can diminish long-term strength and muscle gains. The cold suppresses the inflammation and muscle-protein synthesis signaling that normally occur after resistance training, thereby reducing the hypertrophy and strength improvements from the workout. Coaches in sports like track & field and bodybuilding now often advise against icing or cold baths right after training sessions (except perhaps during competition week) because they want to allow the athlete’s body to undergo its natural adaptive process. In other words, some degree of inflammation and soreness is a necessary part of getting stronger and faster.

In endurance and team sports, the picture is a bit different because the priority is rapid turnaround and performance in the next event. Sports with congested schedules – for example, professional soccer or basketball – do still rely on modalities like ice baths and cryotherapy for acute recovery. Athletes frequently report feeling less sore and more ready to perform the next day after an ice bath, which can be crucial when they have games night after night. However, even here the scientific evidence is mixed. Research has found that many of the benefits of cryotherapy are perceptual: athletes feel better or fresher, but objective measures of muscle recovery (strength, jump height, etc.) often show no significant difference whether they used cold water, hot water, or no intervention at all. A recent review noted that much of the positive effect of common recovery strategies (ice, massage, etc.) may come from the placebo effect or subjective feeling of recovery, rather than measurable physiological changes.

Professional sports teams are adapting accordingly. In European soccer, for instance, virtually all teams employ some post-match recovery interventions, but the approaches vary widely: one survey of elite clubs found 74% used water immersion (cold or alternating hot/cold), 70% used massage, and 57% used foam rolling as part of their recovery routines. The focus has broadened to combine methods that address different aspects of recovery – a typical post-game routine might include a light active cooldown on a stationary bike, followed by an ice bath, then a massage and stretching session. The ice bath might help an athlete subjectively feel less sore, while the massage and movement help restore range of motion. Teams are careful to monitor that these interventions don’t impair training adaptations in the long run. It’s become common, for example, for strength coaches to advise skipping the ice bath during heavy training phases (to let muscles fully adapt), but then use them during tournament play or late-season phases when immediate performance is paramount. This kind of periodized recovery strategy attempts to get the best of both worlds: maximizing adaptation in training periods and maximizing short-term recovery in competition periods.

The sports medicine community has updated injury management acronyms from the old RICE toward new ones like POLICE (“Protect, Optimal Load, Ice, Compression, Elevation”) and even PEACE & LOVE for soft tissue injuries, which emphasize gentle loading and movement early after injury rather than complete rest. Across sports, there’s a recognition that complete immobilization is rarely ideal, even for injuries – and that controlled movement can accelerate healing of muscles and even broken bones. Ice is now seen as one tool among many, to be used sparingly and tactically (for example, to manage pain in the first 24 hours of an injury, or to provide comfort after an exceptionally strenuous event), but not as a blanket solution for recovery.

In summary, while the particulars differ, other sports are largely aligning with what baseball is learning: the key to recovery is circulation and gradual return to function, not simply icing everything down. Whether you’re a pitcher, a runner, or a basketball player, the modern recovery playbook leans more on active modalities (movement, therapy, and thoughtful rest) and less on passive ice. The once-universal image of athletes constantly icing their knees, shoulders, or elbows is slowly giving way to scenes of athletes on foam rollers, in compression boots, or doing mobility drills. This cross-sport evolution underscores a general principle backed by science – the body heals better when you support its natural processes, rather than trying to short-circuit them with excessive cold.

Conclusion

From the 1970s to today, the perspective on icing in baseball has come full circle. What began as a well-intentioned remedy – a simple ice pack to calm a fiery pitching arm – became almost dogmatic in baseball culture for decades. However, as we’ve detailed, modern medical research failed to validate the assumption that icing aids recovery; in fact, it revealed quite the opposite, that icing often delays recovery and healing. This insight has triggered a major shift in how pitchers care for their arms. Today’s best practices favor an active, comprehensive approach to recovery: promoting blood flow, maintaining mobility, and supporting the body’s innate healing responses through proper training, nutrition, and rest. Icing, once the centerpiece of post-game routines, has been relegated to a minor or situational role.

It’s important to note that ice is not inherently evil – used judiciously, it can still help with immediate pain or acute injury management. But the blanket “ice after every outing” policy has been dismantled by evidence and experience. In its place is a recovery model that trusts the body’s design: exercise creates micro-damage, the body responds with inflammation and repair, and that process (when supported by movement and good habits) makes the athlete stronger. Suppressing that process with ice and drugs can hinder full recovery. Baseball, like many sports, has embraced this new paradigm. Pitchers are now recovering smarter and more naturally, and as a result, they’re staying healthier and performing better over the long run. In the end, the evolution of icing in baseball is a case study in sports science progress – showing how even deeply entrenched practices can change when players and coaches follow the data and prioritize what truly works for performance and health.

Sources:

The information in this artile is based on peer-reviewed sports medicine research and expert opinions, including findings published in medical journals and insights from MLB training staff and sports scientists. The shift away from icing is documented by researchers like Dr. Mirkin (who coined RICE) reversing his stance, and by analyses in training literature demonstrating ice’s inhibitory effects on muscle recovery. Current MLB recovery practices and recommendations from pitching coaches (e.g. Driveline Baseball, National Pitching/Tom House programs) have been cited to illustrate the real-world application of these findings. Comparable trends in other sports have been referenced from sports science reviews and cross-disciplinary studies on cryotherapy and recovery. All cited sources are listed in-line for further reading and verification.

TLDR: Summary of Key Points

- Icing pitchers’ arms after games became popularized from the 1970s onwards.

- Modern research shows icing can delay rather than speed up muscle recovery.

- Inflammation is essential for muscle healing; icing interferes with this natural process.

- Sports medicine now promotes active recovery methods (movement, muscle activation, and therapeutic exercises) instead of passive icing.

- Major League Baseball (MLB) and professional pitching programs increasingly adopt comprehensive recovery strategies focused on mobility, soft tissue therapy, and holistic care.

- Icing is recommended selectively for acute pain or injury management, not as a standard post-exercise recovery practice.

I have had the privilege of coaching Youth Baseball for over 20 years. During that time, I’ve coached all ages from T-Ball to 18U, at the House League, Select, and Rep levels. Over that time, in the constant pursuit of learning, I’ve picked up multiple certifications from Driveline Baseball, as well as Blast Motion, Scout School 360, and NCCP. I’m honoured to be an ABCA member. Articles on this site are mostly inspired by people smarter than me who have done extensive scientific and real world research. As I gather their info and try to form cohesive ideas and strategies from it, I record that work here.

Recent Comments